Unlike the rest of my blog, this post is not about one specific spot, like the Ditch or Lutherville, or even thematically grouped, like launch ramps or mini ramps. It is instead about two very different places, Towson and Lansdowne, and two very different styles of skating, street and concrete flow parks. I had considered splitting this up in to two separate posts but decided to keep it together because I find the juxtaposition of these two places interesting. While they are quite dissimilar, what they have in common is that, in my last two years of high school, both of them were frequent destinations. Once we were old enough to drive many more spots opened up to us. We visited other backyard mini ramps, as I talked about a couple months ago, and took day trips to indoor ramp parks, such as Rip the Lip and Cheapskates in Pennsylvania. More often than not though, when we wanted to skate something besides one of our ramps, we drove to Towson or Lansdowne.

Despite all of the ramp and park skating I’ve written about previously, I skated street just as much. That was how I started skateboarding and I never stopped doing it. All that changed was that, as I discussed in my first post, where I skated expanded as I aged. I started by tic-taccing on my patio. I progressed to the banked driveways on my street and then the curb cuts in front of Eddie’s house. Next was the loading dock at our elementary school and then the small steps and ledges at the middle school. After that were the painted curbs, parking blocks and manual pads at the office buildings and strip malls on our side of York Road. As a teenager, I began to venture over to the other side of York Road. There was a small business district and industrial park on a service road back there. The fronts of these businesses had more curbs and parking blocks as well as small stair sets. The rears had more interesting features, including a number of different loading dock and bank configurations. I became familiar with this area in a way that only skaters can understand. We explored it daily, aimlessly wandering around looking for new things to skate. There weren’t any real “spots”, nothing that you would skate for any length of time, just a variety of random obstacles that you would hit and then move on. For example, early on one of the best “spots” was a bunch of plywood stacked against a dumpster behind a Dunkin’ Donuts. That was probably the first ramp-like thing I ever skated. It only lasted about a week but Eddie and I skated it daily. Another favorite was a large slanted rock that sat in grass, a foot or two back from the entrance to a parking lot. I would ollie up on to it, do something like a rock ‘n’ roll and then pop back off. I loved that stupid thing. It’s what I had, just small steps, red curbs, propped up wood, loading docks and rocks. There weren’t even any good ledge spots, none that slid anyway.

During middle school and the first half of high school, this is where I normally skated if I wanted to skate street. The fallback spots were always different schools. There would always be at least one stair set or bench to skate at a school. During the summer, my father used to umpire for an adult baseball league and I would often accompany him to the games. These games were frequently held at some of the nearby colleges, which were always great fun. These campuses always had some interesting plazas to skate. They were empty in the summer, large and exciting to explore. Yet, besides various schools and colleges, there wasn’t very much else that I skated. There were several nearby parking garages, with slick curbs, that were our rainy day spots. I occasionally skated in Cockeysville, the next neighborhood to the north, but it was a bit too far for me to skate to regularly. The only spot of note there was a short steep handrail, one of the very few I could boardslide.

Once we old enough to drive, we skated a much larger variety of street spots. That sounds odd, driving somewhere to skate street, but what it normally entailed was checking out a spot someone had heard about or simply exploring another nearby neighborhood. Despite being so close, I never skated Baltimore City itself very much. I was in the city all of the time, for punk shows, art events and record shopping but I didn’t really skate there. I don’t know why that is. It may be because a lot of the city sucked for skating. I know now a bunch of Baltimore street skaters are going to find this, call me a poseur and tell me that the city was great for street skating. Maybe it was? Maybe I just didn’t know where to go? There didn’t seem to be that much. The hip neighborhood at the time, Fells Point, was unskateable. It had a skate shop, a punk record store, a coffee house and a bunch of bars. It was where all of the “alt” younger people hung out, but the streets were cobblestone and the one main plaza was made of chunky brick. If that plaza had been smooth, it would have been a different story. As it was, there was no localized place to skate. All of the decent spots were scattered about the city.

I spent quite a bit of time at Maryland Institute of Contemporary Art. I took evening and weekend art classes there. There were two spots nearby, a three block monument near the Lyric Opera House and some killer banks at the Lyric itself. The three block was frequently skated, the Lyric was unfortunately almost an instant bust. Nearby on Charles Street, there were a few parks and office buildings with smooth ledges but it quickly became hilly and hard to skate. The rest of the spots I knew about were downtown. There were some nice banks at the Legg Mason building and a huge courtyard of black marble at another office building across the street but those were also quick busts. You couldn’t skate most of the Inner Harbor either. The southern side of the harbor was not as built up back then. By Federal Hill it was largely empty and safe to skate but all that was there were some big steps and rough concrete ledges. Beyond that, I can’t think of very much else. Large sections of the city were frightening and we only braved them for punk shows, so instead of skating the city, we skated Towson. That was our safe suburban version of city street skating.

Towson is one neighborhood to the south of where and I grew up and the Baltimore County seat. It is much more of a town than the suburbs surrounding it. It is also home to a large university. I went to that university often, to use the library, see bands play and also to skate. It had some huge stair sets that always looked tempting but were way outside of my ability. Besides that, there were a couple brick plazas with stone benches and ledges, none of which was particularly good to skate. Towson, the town, was much better. Our skating there was similar to my earlier local street skating. We would park and wander around, skating various, not particularly noteworthy, things. What made it so good was that it was dense enough that there were numerous places to skate within short distances of each other. You could easily spend a whole weekend day there; there were that many different minor spots. There were a couple of office buildings with small stair sets and ledges. There were some mellow banks, loading docks and small gaps in the parking lots behind the college bar. One of the parking garages at the mall had adjacent curbs to banks at its entrance. It also had a paved to smooth transition jersey wall up top. For a while, our local skate shop, Denny’s store Island Dreams, was in Towson as well.

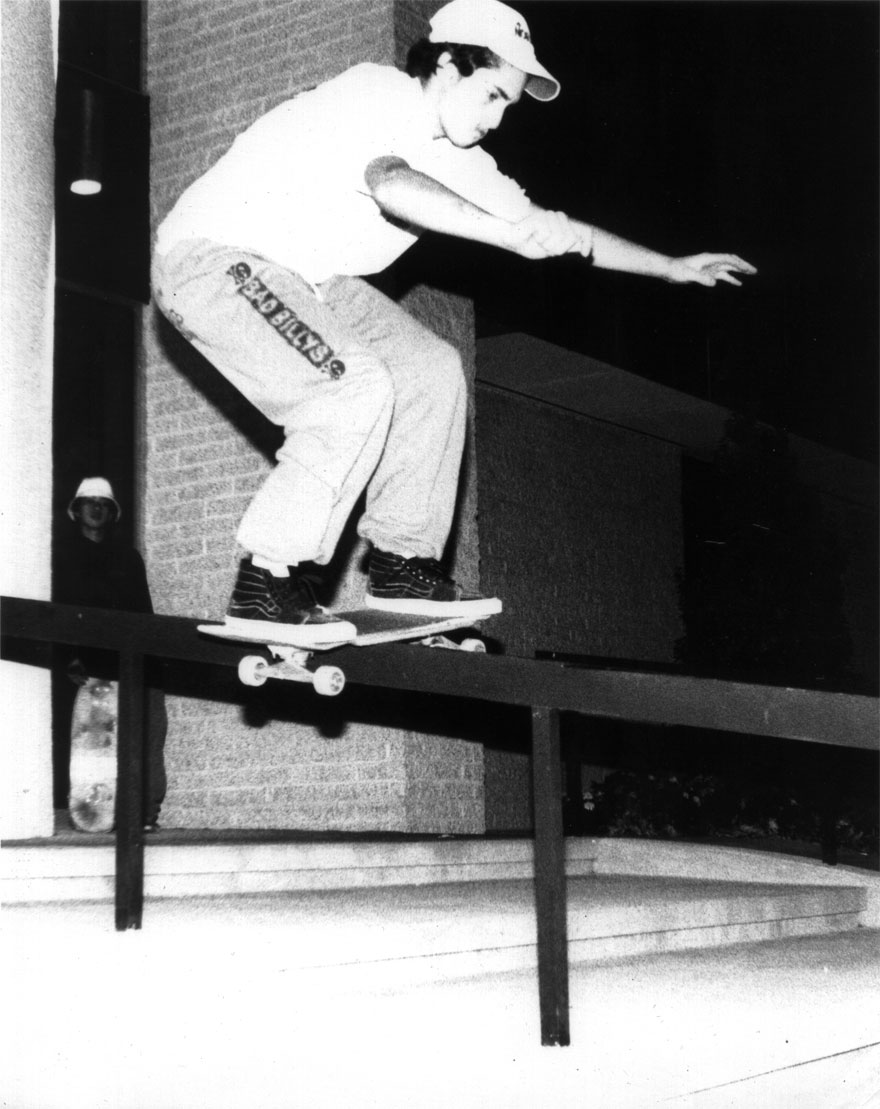

Jeff B with a boardslide on a mellow rail. It’s similar to the Towson courthouse rail but I think this one was at a church. Notice Young looking ’90s stylish in the back with his bucket hat. Again, 1991-ish.

When we skated Towson it was rare that we would run into any other skaters. The only place this happened was at the Burger King. That parking lot had a small curb to tiny bank to curb thing by the drive in window. You could skate it like a bank, a gap or slanted manual pad, getting tricks up and down it. It was annoying because you couldn’t skate it if there were cars in the drive through, so there was a lot of waiting around. My group of friends never spent much time there but, for some reason, this was a very popular spot for other kids. Years later, when that Burger King closed, it looks like it became a steady spot. You can see some footage of many kids skating it here. In my opinion though, the best spot in Towson was the courthouse. It was the central attraction for me and was surprisingly safe to skate if you went after work hours or on the weekends. The interior plaza was lined with marble ledges and there was a small fountain in the center. The ledges also ran parallel to the multiple stair sets on the sides. You could bomb and ollie off of the bigger of those banked ledges or grind and slide down a set on the smaller ones. The main interior entrance to the courthouse had a long, mellow and square handrail as well. Jeff B was the only person I know that ever skated that. He boardslid it, though I think he may have caveman-ed in to it. Back then, any rail over four or five steps was complete madness, nowadays I can only imagine the tricks that kids could get down it, but looking at pictures on the internet it appears that it may now be knobbed. The best part of the courthouse was the “front”. The front faced a big, six lane bypass road that swung around the center of Towson and connected to Towson University. There was no street parking on this road so no one ever used that entrance. You could always skate there. No one would ever kick you out. The marble ledges here sloped from barely curb height up to about two feet, and, most importantly, those ledges flanked the small stair sets, so you could get grinding or sliding tricks off of them. It was by far the best spot I knew of. Looking at video of it now it appears that, post 9/11, they put in some large spherical security sculptures that are in the way of the step ledges. Despite that, it still looks fantastic.

My “holy grail” spot in Towson was one that I only able to skate a few times. Behind a mechanic’s garage was a small parking lot and the back walls of that lot were two high, steep banks. On the rare occasions that cars weren’t parked there you could ollie the curb up in to those banks. If you got enough speed, you could try to bash through the nearly 90-degree transition from one bank to the next. That was it. It was tight, awkward and hard to skate. It was a fairly shitty spot. I think I liked it so much because it was so hard. The challenge was to simply see if you could skate it, not do any tricks. That appealed to me.

While you can divide skateboarding up like a sport, into various disciplines, I like to think of it as being much closer to an art. Seen this way, I consider skateboarding to have two major forms of expression. The shorthand for these would “tricks” and “style”. I’m not completely happy with either of those terms, they are both somewhat limiting to what I am actually trying to talk about, but they are close enough for now. The best skaters have both of these things. They can do hard tricks and look good while doing them. I’m sure anyone reading this who skated has seen people with just tricks. You will find one at every skate park. There is always a kid who can do some insanely technical tricks but otherwise looks like he has never stood on a skateboard before. All style is the opposite, someone who looks good and comfortable on the board but can’t do even the most basic tricks. I was never that good and I am never going to be good, but I aspire to a happy balance between these two things. Similarly, this concept applies to the various disciplines I dismissed earlier as well. I think it is important to be able to skate all different kind of terrain. To have, what in sports would be called, “the fundamentals”. I think the street kids who can do insane flatground tricks but can’t kickturn on vert are doing themselves a disservice and the same holds true for the bowl rippers who can’t ollie up a curb. I think it is important to be well rounded. Of course, this is all a matter of personal preference, anyone can skateboard however they please, but that is a rather adult and enlightened opinion. As a teenager, it “mattered” how you skated.

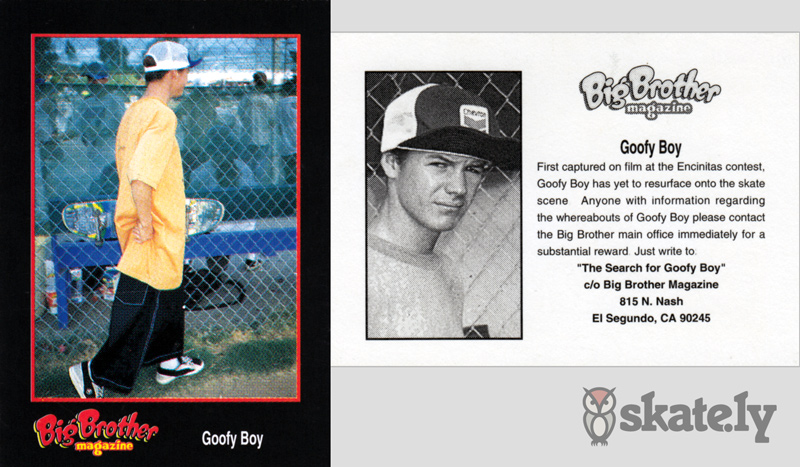

Source: Skately. Goofy Boy from Big Brother Magazine.

What happened at the dawn of the ‘90s is that the focus in skateboarding became almost solely about tricks and street to the detriment of all else. Freestyle, the red headed stepchild of the skateboarding world, had clung on through the ‘80s. We all had a grudging respect for freestyle, mainly because the tricks that Rodney Mullen invented were so incredibly hard. It was not cool though and there was only one Mullen. There were many other people in short shorts and high tube socks, doing tricks straight from the ‘70s. It was lame compared to the high speed aerial assaults of vert skating or the bad boy image of street skating. At the end of the ’80s both vert and freestyle died. The whims of skateboard fashion shifted to pure technical street skating and, ironically, that style of skating involved adapting many of Mullen’s freestyle tricks to the street. The pogos and handstands from freestyle went away but the flip and spin tricks were now what all skaters aspired to. It was freestyle skating, just with the short shorts and tube socks replaced by big pants and small wheels. If you didn’t skate in the early ‘90s it’s hard to explain how ridiculous the fashion was. We would go to thrift stores or big and tall shops and literally buy the largest pants we could find. We belted them on with shoelaces or twine. You would cut off the legs to fit, so they hung over your shoes, and, not being hemmed, these, of course, would quickly fray. It was especially cool if these pants were mustard yellow or acid green or some other ridiculous color. This look was colloquially known as the Goofy Boy. Granted, the worst of this was around 1994, after I had all but stopped skating and was flirting with rave culture, but I still, briefly, dressed like this. The same went for wheels, well… not exactly. With wheels, it was just as extreme but in the opposite direction. You bought the smallest wheels possible. There was a race to the bottom. There was no reason to it. There were some rationalizations made about smaller wheels giving you a lower center of gravity and that may have had some miniscule difference in making pressure flips easier but it was really only fashion. What this meant was that now skateboarding was a bunch of guys in clown pants rolling slowly around in a parking lot, staring at their feet and trying complicated technical tricks for hours on end, rarely landing anything. It was an important point in the progression of skateboarding, but in actual practice, it sucked.

This style of skating was too technical for me. I couldn’t do most of the tricks and I thought they looked bad so I didn’t put any real effort in to trying to learn them. I picked “style” over “tricks”. It was not the kind of skateboarding that I wanted to do. In the tribal manner of high school, I identified as a skater but I was so immersed in the skateboarding sub-culture that that alone was not enough. It was important to me to further distinguish myself, as to what ”kind” of skater I was. It was clear that I was not a technical street skater. Though I largely skated mini ramps what I had always wanted to be was a concrete transition skater. I felt more comfortable on concrete walls and it just seemed to me to be somehow cooler. I had grown up with the magazines full of images of the old California parks, pools and bowls. We didn’t have anything like that in suburban Maryland. We didn’t have Del Mar. What we did have was Lansdowne.

Lansdowne was infamous for a number of reasons. It was in a poor, rough area. It seems almost trite to say that at this point, but that was one of its defining characteristics. Its other major feature was that the park itself was complete anarchy. There were no rules and no supervision. As I learned when I interviewed Denny, built at the end of the ‘70s, Lansdowne never even properly opened. “The concrete bowl was supposed to be part of a larger park to be built in 1980, but an arson fire stopped construction, and the county abandoned the project. This left the park in the hands of the skaters, who picked up the trash [and] swept up the stones[.]” The skate park wasn’t filled in or torn down, it was just left unattended, unsupervised and uncared for in a field for the next twenty five years.

Lansdowne was on the south west side of Baltimore, in a small field wedged in a corner between two highways and an apartment and townhouse complex. I credit Young with first telling us about it. He had lived nearby and skated it before moving to Cockeysville. To get there we would drive west on the Beltway, around the city, and get off at the exit after the Colt 45 brewery. We would park in one of the many nearly identical parking lots of the housing complex. Drab plain brown brick and relatively nondescript, these homes didn’t look all that different from similar developments in my wealthier section of Baltimore County. To get to the skate park you would walk a dirt path back between two of these apartment buildings. This is when then the poverty and neglect became more obvious. The chain link fenced backyards bordering the park were not manicured lawns. Instead, they were filled with trash and standing water.

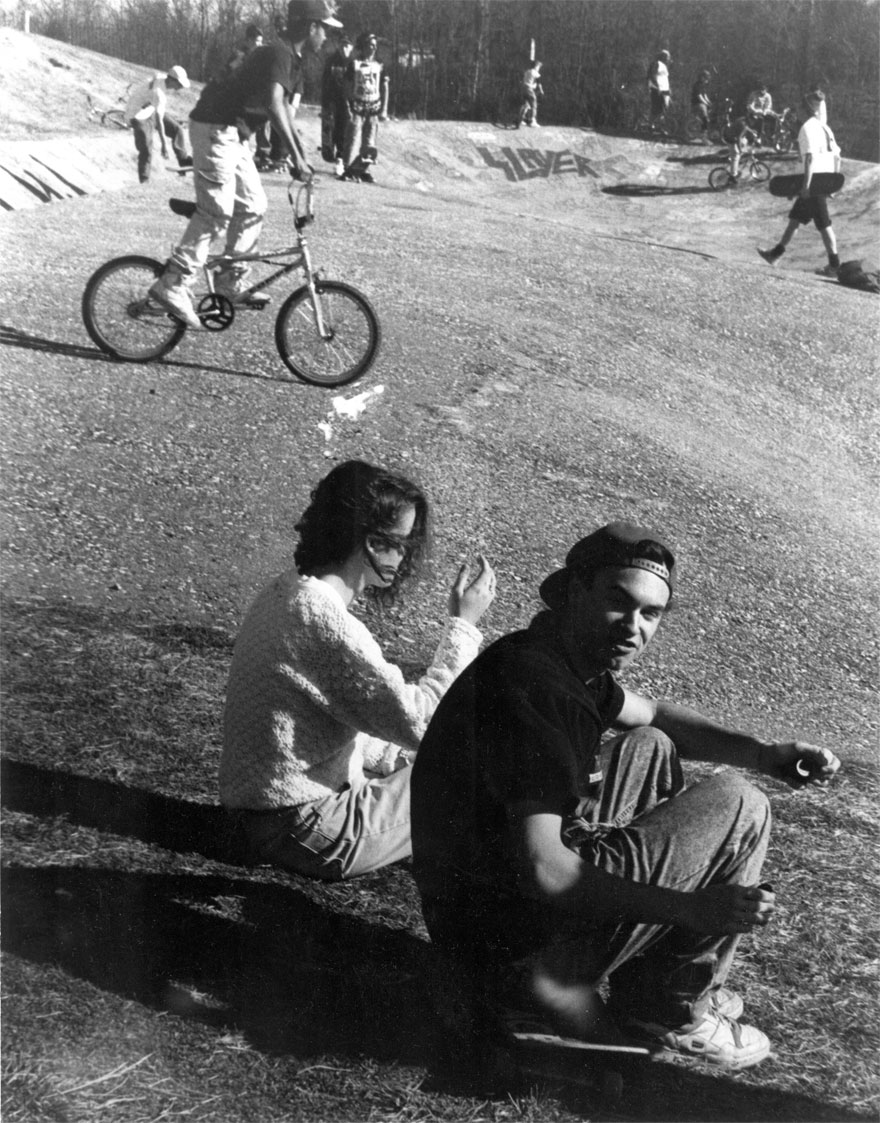

Lansdowne 1990-ish. That’s me seated in the front. Marc is in the background, behind the kid on the BMX.

Cousin to other similar parks like the Dish, the Bro Bowl and the original Ocean Bowl, Lansdowne was one of the few ’70s parks left in the country. It worked like this, at the top of the hill, by the entrance path, there was a flat circular starting area. From there two snake runs branched out. They both started as small tight drainage ditches. The outer one looped out around the end of the park, widening as it turned. The interior one dropped more quickly and widened as well where it made the sharp turn around the hip. Both snake runs emptied into a large, flat rectangular section with banked walls. This area had a few random humps and bumps spread around the flat. An extremely mellow saucer of a bowl was attached to the outside of the longer snake run, right before it met the flat area. Large areas of “deck” along the top were also paved, but poorly. Up there it was cracked, rocky, bumpy blacktop, almost like gravel. A typical run at Lansdowne would normally go like this, you would carve down the outside snake run, swing high up on the wall around the turn, try to hit the wall opposite the bowl as high as you could, come back down into the snake run and bounce over the other side into the bowl. A long frontside or backside carve around the bowl would leave you with barely enough speed to make it back up over the hump again and into the flat rectangular section.

Nothing had a lip. Everything was rounded in that ‘70s style, so unless there was a parking block set up somewhere, lip tricks were out of the question. The two best places to skate were the hip and a small oval bump in the flat section. This bump was named the Smurf because it was painted blue. We would push across the rough gravelly flat at the top and ollie the hip or air out of it. We did similar tricks, on a smaller scale, on the Smurf. That was it besides skating the flat section like a ditch. If you were “good” at Lansdowne, it wasn’t because you were doing many tricks because there were very few places to actually do those tricks. The terrain had an equalizing effect. Being good at Lansdowne just meant that you knew how to skate. It was my style of skating, just carving walls and doing ollies. I enjoyed that much more than the boredom and frustration of trying flip tricks in a parking lot. While I appreciate the discipline it took for kids to work endlessly on those tricks that wasn’t my way of learning. I just wanted to have fun and let any new things I learned develop much more organically. Now that everyone is so good, I’m sure kids can bust some amazing tricks over that hip. Back in 1990, everyone was still struggling to do those tricks on flatground, so the best skaters at Lansdowne then were the ones who could skate the fastest and ollie the highest. Even Natas, one of the best street skaters in the world at the time, only got an ollie or two here in his part from Speed Freaks in 1989. There was always a legend that someone ollied out of the small snake run by the hip, over the wide channel of the outside one and in to the bowl. I’ve found video of a guy, Matt Dove, attempting it and breaking his leg. He wasn’t even close. It’s a huge gap even by today’s standards. I wonder if it anyone ever made it or if that was all just childhood stories.

There were never any adults at Lansdowne, just hordes of feral children. There were no bathrooms and no water fountains. The closest convenience store was driving distance away. I know I’ve talked about the Ditch and Lutherville being lawless but they paled in comparison to Lansdowne. I was always a little on edge there. I’ve been trying to figure out why. It was in a rougher area and isolated but I think my fears were class based and largely unfounded. It wasn’t dangerous, per se. I never heard of anyone robbed or run out of there, like the stories you hear about the Dish or the Bro Bowl. I saw some minor squabbles and fights, but not anything particularly bad. There were always occasional fights at skate parks. The local skaters weren’t friendly but it wasn’t “blatant localism” either. It wasn’t like you were trespassing on someone’s secret spot. The place was crowded and frequently saw skaters from as far away as Pennsylvania or DC so the majority of kids there were usual not local. The non-skating locals would sometimes wander over in to the park and play at intimidation, but again they were normally outnumbered. Some of the edginess of the place was obviously a result of our age. Teenage boys tend to group together and look askance at anyone outside of that group.

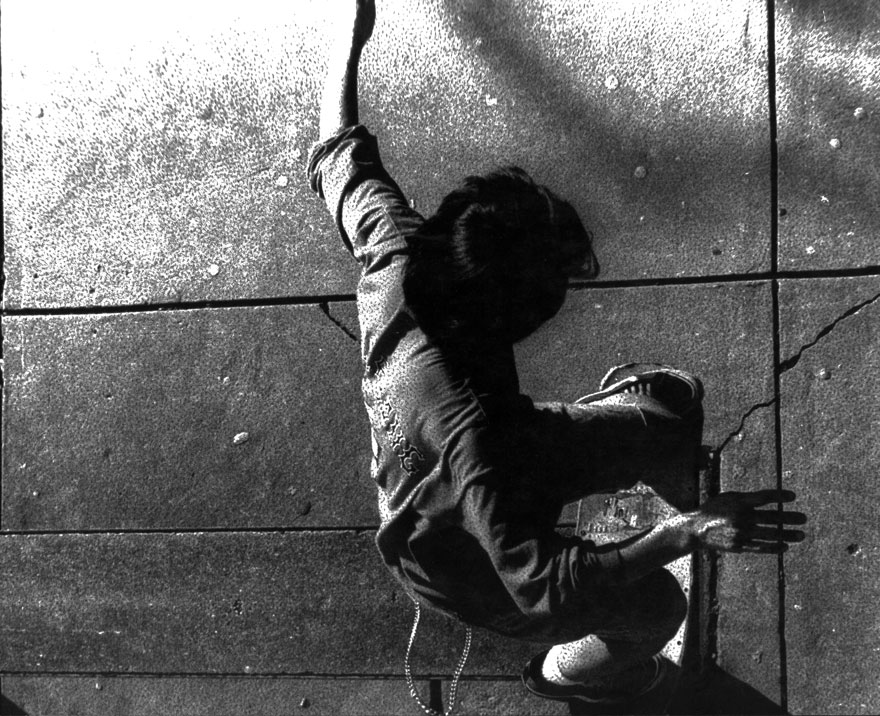

Your author at the tail end of a one foot ollie out of the hip at Lansdowne, some time in the very early ’90s.

Largely though, I think the bad vibes were a product of the times. Much like big pants and small wheels, vibing was also in style. Skateboarders were hated. They are still hated but at least now people are used to them. We came of age during the birth of modern street skating. It was all new and no one knew how to react appropriately to it. The current solutions are to knob things and build skate parks. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s the solution was make it illegal, everywhere. The justifications were always the same, liability, pedestrian safety or property damage, but the heart of the matter was that dirty, sweaty kids repurposing the urban landscape for their own enjoyment violated some unspoken sacrosanct sense of order. It drove some people mad. Skateboards were banned at schools and, in some cases, entire towns. Cops arrested children for skating in empty parking lots, security guards overstepped their bounds and attempted to fight teenagers or confiscate their boards and random concerned citizens would verbally and physically accost young adults in public over their choice of leisure activity. All of this still happens to this day, but in the early ‘90s it was ever present. Skaters were viewed as public nuances at best, criminals at worst. Skateboarding was the physical activity of choice for weird, creative kids who weren’t afraid of getting hurt. Instead of being cowed by this negative stereotype, they chose to embrace it. The mellow, easier going surfer image of the ‘80s California skater was replaced by the much harder-edged, urban street skater of the ‘90s. The videos ceased being the goofy, lighthearted fare of the early Powell Peralta videos and began to include footage of all the varying bad behaviors, the drugs, alcohol and fights. The irreverence and anti-social outsider attitude that Thrasher had championed was taken to offensive new heights when Big Brother Magazine debuted in 1992. Being an asshole had come in to fashion and this bad attitude was democratic. It was evenly spread around. It wasn’t solely reserved for authority figures, it was applied to other skaters as well.

Lansdowne was one of the few places where we interacted with large groups of other skaters that we did not know. This made the vibing, shit-talk and snaking especially obvious. It really wasn’t that bad but I made an end run around it and decided to avoid it altogether by avoiding the crowds. I went really early on the weekends. I did this often enough that I took to keeping a push broom in the trunk of my father’s car. We would frequently be some of the first people there and would inevitably have to sweep out the broken beer bottles from night before. The skaters were the ones who took care of the place. While filthy and absolutely covered in graffiti most of the surface of the park, outside of the gravely deck, was in surprisingly good shape after years of neglect. There were very few cracks. Whatever drains it had must have still worked because there would sometimes be small puddles but it never filled with rainwater. It somehow, miraculously, stayed like this for more than twenty five years. I don’t know how that is possible. There were a number of other remnants of ‘70s parks in the area, all of which were virtually unskateable just a few years after they closed or were abandoned. Even more miraculously, Lansdowne is still there. Around 2004 the County began to clean it up. It was patched, the tops repaved and pre-fab ramps were put in next to the original park. It now has full pad rules and hours, which does seem to somewhat tarnish its legacy. I guess it exists now more for beginners, old men on nostalgia trips (this old man will probably skate it in the spring) and long boarders, than for anyone else. Still, I suppose it is cool that a living piece of skateboard history has been preserved.

Below is some more awful quality video of Jeff B and I skating it in 1991.

This was good to see. I practically lived at the bowl between 87 to 90. And the rumor was Julien Stranger ollied the gap into the bowl.

Nice article on Lansdowne. You captured the vibe of the place really well and you described my favorite run starting on the upper snake run perfectly. We liked to run doubles on that run and pass each other by carving on the high wall before entering the bowl at the end. It was a blast and I think the edginess of the spot was part of the appeal. My friends and I went up to Lansdowne from NOVA around 1986-1988. Would love to go back sometime to ride that epic snake run but I’m afraid the true vibe of this spot has been long lost.