This post is coming in well late. Of course I have no real deadline but I’ve tried to keep to a roughly once a month schedule. I struggled with this one. Writing about the past is much easier for me than writing about the present. So let me start this off by rehashing a bit of skateboarding history. It has a point, I promise.

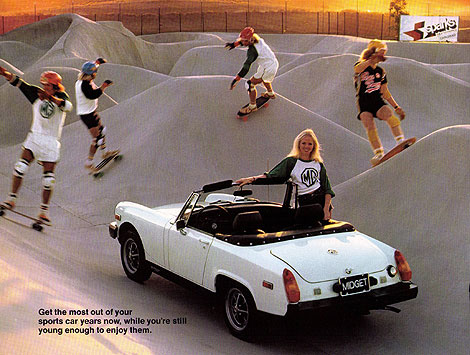

As I’ve discussed in many of my previous posts, skateboarding has gone through a number of different phases. The initial sidewalk surfing fad of the ‘60s faded quickly but rose again in the mid ‘70s, thanks largely to advances in equipment, such as the invention of the polyurethane wheel. Pioneers like the Z-Boys pushed skateboarding out of the streets and in to pools. By the late ‘70s, a glut of skate parks opened up across the nation to cater to this new trend of transition skating. Almost all of these parks would close by the end of the decade. Commonly referred to as “when skateboarding died”, what this did was force the remaining skaters to build their own spots, in the form of backyard vert ramps. These ramps, and the scenes that developed around them, ushered in the mid ‘80s vert craze and the height of skateboarding’s popularity. The kids of this Bones Brigade generation (your author included), not having access to skate parks and too young to build their own ramps, took to adapting vert tricks to the street. This was the first wave of modern street skating and it was marked by launch ramps, street plants and bonelesses. Branded “street style” by the professional contest circuit, it joined the two other existing disciplines, freestyle (which was essentially just flat ground skateboarding) and, of course, vert.

By the end of the ’80s both freestyle and vert died. Many of the freestyle tricks invented by Rodney Mullen merged with “street style” in to the new form of street skating that took over in the ‘90s. This style of skating, technical tricks done on re-purposed parts of the urban environment became the dominant form of skateboarding for the next two decades. Vert skating made a comeback of sorts, in the form of corporate sponsored televised contests, but that was only for professionals, the kids all skated street. No longer confined to skate parks or backyard ramps, skaters swarmed to urban plazas and the marble courtyards of office buildings. This caused a major backlash and the public quickly began to see skateboarding as a nuisance activity, associated with petty crime and property damage. Overzealous private security guards and town ordinances banning skating in popular public places, such as Love Park for example, left skaters “kicked out of everywhere” and with limited options. Skate parks in ’90s and early 2000s, at least here on the east coast, were few and far between. Outside of the remnants from the ’70s and the few private indoor parks, the public skate parks that did exist were often pre-fabricated metal ramps. These tended to be generic and, not built by skaters, poorly planned out. Designed for small children, they also generally had strictly enforced hours and pad rules, both of which were anathema to the lawless undercurrent of skateboarding culture.

While backyard ramps never completely went away, what happened in the ‘90s was that DIY spots began to replace them. The concept of DIY was nothing new. Since skateboarding began skaters had been propping up pieces of wood against walls, dragging parking blocks to unused slabs of concrete and placing ramps in public places. Much like the first incarnation of Lutherville, most of these early DIY spots were a temporary rag tag collection of junk. What changed in the ‘90s is that skaters began to pour concrete. The spots became more permanent. Built in abandoned or unused spaces, under bridges or on the foundations of razed buildings, these spots often began as just a few poorly poured bumps and lumps. While generally unauthorized, the places that were isolated enough to avoid detection, or were tolerated and ignored, began to grow. Places like Burnside, in Portland, and, several years later, FDR in Philadelphia, became fully-fledged concrete skate parks, the likes of which had not been seen since the late ‘70s.

Fresh DIY at Ridge. Source: Neverstop Skateboards

Not all of these places were giant transition based parks either. Many of them were just a few makeshift obstacles on a flat plain of concrete. Two in this style worth mentioning are Ridge and the Slab (aka Shantytown) both of which are places that I would have written about, had I not quit skateboarding for twenty years. Ridge was one of the more popular DIY spots outside of Baltimore, and the Slab, which was built on the then undeveloped Brooklyn waterfront, has an entire book about it. There were many, many more. There still are. While outside of the crumbling BQE spot, New York City doesn’t have much; there are two great DIY spots nearby in New Jersey. However, much like how DIY spots mostly replaced backyard ramps, public skate parks are now supplanting the DIY spots.

We are in an absolute golden age of the free public skate park and this is largely due to the popularity and success of the DIY spots. Local governments finally started to realize that the answer to the scourge of skateboarding was not to outlaw it but simply to build places for people to skate. I would suspect that some of this shift in attitude is because the skaters of the Bones Brigade generation are now in their 40’s and, no longer surly disreputable teenagers, are in positions of power that allow them to lobby on behalf of skateboarding. This has led to a massive amount of skate parks built around the country in the last decade. Philadelphia wisely allowed FDR to continue to grow and, attempting to draw people away from the still illegal to skate Love Park, built an amazing open plaza not too far away. Even impoverished Baltimore managed to build a great three-pocket bowl next to a junky DIY spot and create an official Skate Park of Baltimore. They are currently in the fund raising process to re-do the adjoining street section. New York City, being New York City, has an embarrassment of riches. There are almost too many skate parks to name. They are scattered across all five boroughs and range from small manual pads and benches in basketball courts to giant concrete spaces. The two premier parks are in Manhattan, of course. These are LES, the more street oriented park under the Manhattan Bridge, and Chelsea, which is a big bowl and flow park on Pier 62.

Chelsea from above. Source: George Steinmetz in the New Yorker.

I can honestly say that without the skate parks I doubt I would still be skating. They were one of the primary reasons I started again; I wanted to experience something that I did not have growing up. Without them I would have kept at flat ground skateboarding for a while, found some out of the way ledges and then probably gotten bored and slowly tapered off. I often feel a bit guilty that I don’t skate street more. New York City is known for street skating. So much iconic footage and great street skaters have come out of here, but let me tell you, skating street in New York City is hard. Most good spots are busts. Famous places like the Brooklyn Banks have been shut down for years. The roads are all in bad condition. It is intensely crowded and the automobile traffic is incessant. I often long for the smooth empty parking lots, painted red curbs and manual pads of my suburban childhood. If that kind of idyllic environment existed in New York City I would surely skate street more often, but the reality is that I don’t want to hit a pebble and shoot my board out in to the throng of pedestrians. I don’t want to slip and lose my board under a cab. I don’t want to slam and hurt myself in front of a gaggle of tourists. That’s not a good look at 41. Rolling around on transition is much more dignified.

It’s an absolute luxury to have so many parks to choose from. I’ve tried to check out as many as I can, but some of them, like the parks in the Bronx or Queens, are just too far away for me to justify the trip. There are others, like 181 at the northern end of Manhattan for example, that are great fun but because of the distance, I only visit once or twice a year. I now live in south Brooklyn, very close to Owl’s Head, close enough to skate there in fact, but I have relegated that park to what I call my “hangover spot”. As an adult, with a busy work schedule, I can’t “skate every damn day”. I normally skate only on the weekends. If I’m lucky, I may get out twice in one week. So, if I get a late start, or don’t have much free time, I will go to Owl’s Head, but most weekends I get up early and take an hour-long subway ride in to Chelsea. Despite being so far away, it was Chelsea that I made my “local” park.

Chelsea is something of an oddity among the New York City skate parks. The Parks Department has a vague “nothing over three feet” rule when it comes to building new parks. Outside of Owl’s Head and the big metal ramps of Riverside, all of the other parks are small. The Hudson River Park Trust manages Chelsea and it therefore somehow skirted this rule. It’s also unique in that it was built using structural foam, the first of its kind I believe. This gave it a flowing and organic feel, different from the more geometrical or squared off aspects of other parks. It’s located in a large fenced in oval on a pier behind the Chelsea sports complex. Complete with nearby café, park and public bathrooms, it is in an ideal location. Being at a major tourist attraction, it’s also the cleanest skate park I have ever seen, with no graffiti and no trash. It features a large three-pocket bowl up top and a series of banks that drop down around the sides, with ledges, steps, rails, euro gaps and hubbas along them. In the center is a snaking section of banks and transition, ranging from around four feet up to a massive over vert clamshell. It is New York City’s version of Burnside or FDR.

I first began going to Chelsea in the late fall of 2012. As I talked about in my last post, I had initially been too intimidated to go to the popular Manhattan parks. Once my confidence level increased and I finally got up the nerve to go to Chelsea, I largely stopped going anywhere else. I was instantly hooked. As luck would have it, we had a mostly dry winter that year. It was extremely cold but the park was open for most of the winter, unlike the last two years where it has been buried in snow until late March. I would go as early as 8am and, because of the time and the temperature, I would often be one of the only people there. This was good because it took me a long time to get the hang of the place. While it is the kind of park that I had always dreamed about skating, even at my best it would have been too big for me. Some sections in the middle are huge, with easily three feet of vert and even the shallow end of the bowl, at around six foot, is bigger than most of the mini ramps I skated as a teenager. It is also exceptionally fast. Just dropping down the three levels of the banks along the outside was the fastest I had ever gone on a skateboard since I had started back up. I spent my first day there just rolling down and ollieing out of those banks. Over the rest of the winter, I slowly began to relearn my lip tricks on the small quarter and find lines through the center section. That’s about all that I still do there, though I’ve recently taken to skating the bowl more often. While most of it was designed for people much more comfortable on big transition than I am, there are a number of small nooks and odd features that let you get inventive. Up at the top there is a small bump that levels out to the deck of the bowl. It’s a frequent joke among the older skaters that, while growing up, that bump alone would have been a spot. It would have had a name and people would have traveled to skate it. Now it is the most insignificant feature in the park, which really goes to show just how lucky we are to have what we have these days.

While New York may be famous for street skating, it has a strong, though lesser known, history of transition skating as well. There was pool skating going on as far back as 1978, at the Deathbowl. In 1995, Andy Kessler designed and helped build one of New York City’s first skate parks, the ramps at 108th and Riverside. This park is still there and is home to the only vert ramp in the area. Owl’s Head, with its double section bowl, opened in 2001 and was instantly popular. The Autumn Bowl, an indoor DIY spot, was built in 2003 and lasted until 2010. Chelsea opened that same year and has since become the primary destination for transition skaters from the greater New York area. Owl’s Head and Riverside are now often empty on the weekends.

Chelsea, with its bowl, draws a large group of men, and some women, in their 30s up to mid 50s. I’m often at the young end of the age range on weekend mornings. There are many guys, slightly older than I am, that were vert skaters in the ’80s and only skate the bowl. The ones younger than me prefer the more street elements of the park. I am of the age that I straddled both worlds and try to skate a little bit of everything, albeit poorly. I used to refer to the morning sessions at Chelsea as “old man time” until, a few years back, one local told me he preferred the term “gentleman’s hour”. I like that. It sounds much more sophisticated. While Chelsea may skew significantly older than the other skate parks, it has also fostered an entire generation of new transition rippers. This crew, both young and old, and the community that has developed around Chelsea is one of the defining features of the park.

It is, by far, the friendliest skate park I have ever been to. I don’t know if the times have simply changed and skaters are not the dicks they were in the ‘90s, if it is its posh Manhattan location or if I am just old enough that I am immune and oblivious to any attitude, but I have never felt uncomfortable there. Even in the beginning when I knew absolutely no one, I didn’t feel like an outsider intruding upon on a closed scene. By nature I am reserved and a bit of a loner. I generally prefer to do things on my own but once I was skating again I realized I desperately needed skate friends. Sometimes it is fun to have a park all to yourself; you can just put your head down and try the same trick for hours without getting in anyone’s way. Often skating alone gets boring quickly and skating at a crowded park where you know no one can be very intimidating. Having people to skate with makes the entire experience much more enjoyable. Once I began going to Chelsea regularly I made it a habit to act against my nature and to talk to literally everyone. It paid off. I now show up on the weekends and know the majority of the people there by name. I look forward to seeing them. Some have become friends.

Time moves differently as an adult. Even though I feel like I just started skating again, it has been over three years. I’ve been a regular at Chelsea for two and a half. I’ve seen a number of the locals come and go as people move in an out of the city. I’ve seen many people make marked progress, getting much better much faster than I would have thought possible. I’ve made my own progress as well, though at a slower pace. I’ve lost some tricks while gaining others. I’ve seen children grow up there. I will see them in the fall and then, come spring when the park is finally free of snow, I will see them again and they are easily a foot taller. That one is strange to think about. Lutherville, at least the metal ramp version of Lutherville, lasted at most two summers. Jeff B had his vert ramp for one summer. Dookie ramp lasted only two years, I think. Chelsea has already been there for five years. In twenty years time one of the local kids is going to be writing his own blog of skateboarding memories and Chelsea will be where he spent the majority of his childhood. There is now a stability that didn’t exist when I was young. Chelsea is one of the best skate parks I have ever been to and it will be there for years to come. It won’t randomly get bulldozed or torn down. It won’t get knobbed or fenced off. The kids really don’t understand how good they have it, but I’m glad they do have what they have and I’m glad it wasn’t too late for me to enjoy it as well.